Madagascar: The Exotic and Intriguing Grand île (Big Island)

Signs of economic improvement for one of the world’s poorest countries

My first visit to Madagascar

It was August 1990. Earlier in the year, the South African President de Klerk had announced the unbanning of the African National Congress and his government had released Nelson Mandela from prison. These major decisions were followed quickly by numerous official contacts and friendly approaches from other previously-hostile African governments. Africa analysts and observers were particularly surprised by an invitation from President Didier Ratsiraka for President de Klerk to undertake an official visit to his country. The Madagascan president had been an especially ardent and outspoken opponent of the apartheid regime.

I was fortunate to be invited on this visit as a member of the South African business delegation that accompanied the high-level government delegation. Our chartered passenger aircraft followed behind the presidential plane which landed at the Antananarivo International Airport, tucked between the alarmingly steep hills of the island’s highlands. As we descended the stairs to a VIP welcome, I noticed that the old South African flag had been hung upside down. (Clear evidence of long absence of contact and hence familiarity between the two countries.)

The official visit programme comprised a few long meetings in crowded halls, addressed by the politicians from both countries who each declared their firm intentions to re-establish trade and cultural links. The informal component of the visit agenda included visits to the casino, the market place, and long, boozy lunches and dinners, during which many delicious zebu steaks were consumed. (The short-horned zebu is a unique cattle type reportedly created by inter-breeding zebu cattle from the near east and sanga cattle from Africa.) The market was especially interesting, and we saw unique products such as vanilla pods in colourful woven baskets for sale.

I have since undertaken a number of business assignments in Madagascar.

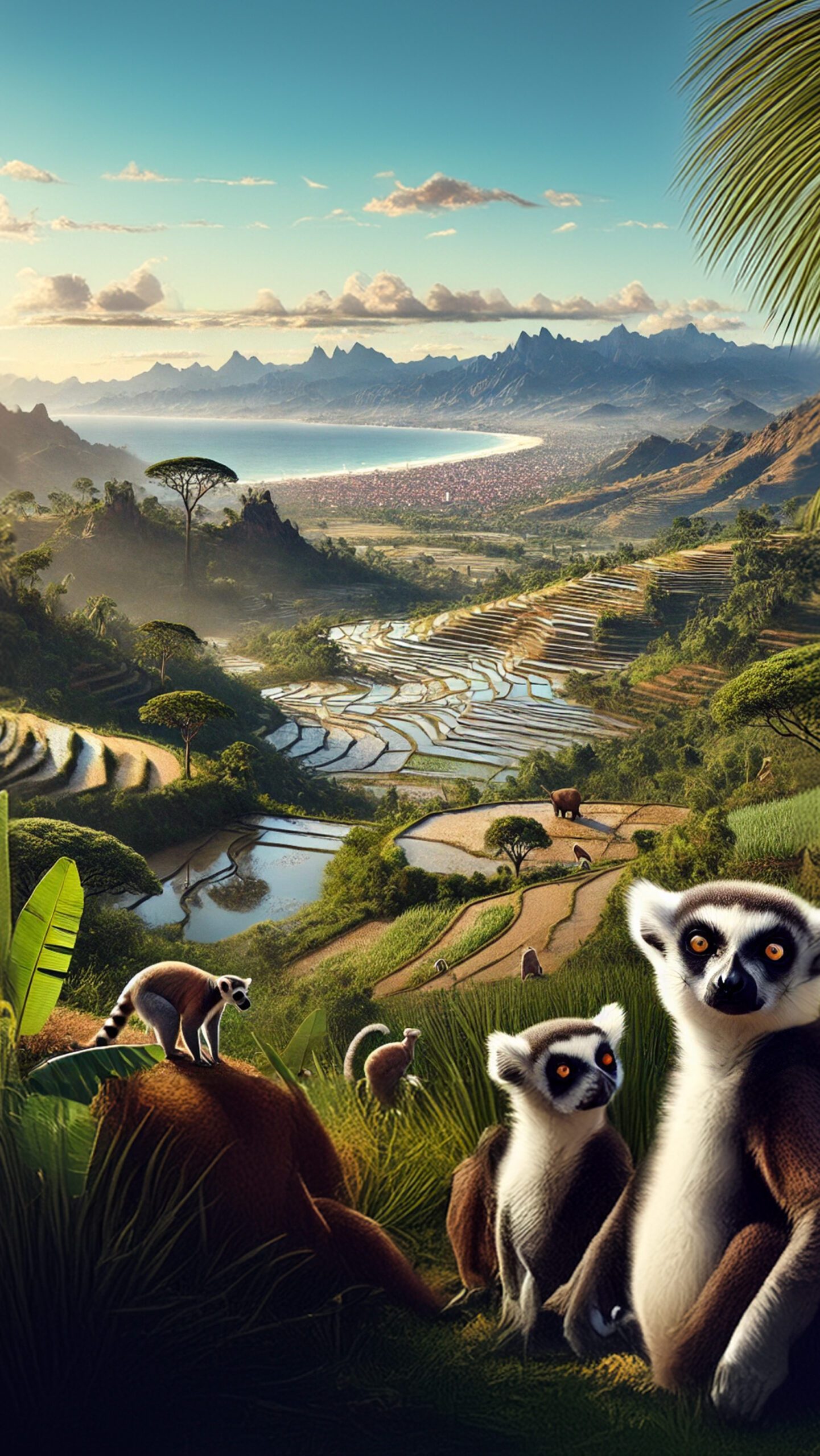

Some economic perspectives

Madagascar lies off the south-eastern coast of Africa. It is separated from the continental mainland by the 400-kilometre Mozambique Channel. It has a land area of almost 582 000 square kilometres and a total coastline length of about 4 800 kilometres. Its mountainous central plateau, (on which the capital, Antananarivo, is situated), is surrounded by low coastal plains. Much is savannah grassland, but there are tropical rainforests in the east. These have sadly been badly depleted by human incursions, with major detrimental effects on the island’s unique flora and fauna. There are reports that many of the primate lemur species are facing extinction.

The world’s fourth largest island is one of the world’s poorest countries. The World Bank estimates the poverty rate at nearly 81% of the population of some 30 million. Subsistence agriculture is the dominant economic activity. Flying into Antananarivo, the first sight from the window is of rice paddies and the green terraced fields on the hill slopes. It looks more Asian than African.Cash crops include coffee, cotton, sugar and sisal. Madagascar is well-known for its production of vanilla, and some 80% of the world’s supply of vanilla beans is from the island. The long coastline makes fish and seafood another major economic source.

The island’s unique flora and fauna as well as its coastline give it much tourism potential. Nose Be in the far north is globally recognised as an ‘adventure’ tourism priority.

The past few decades have been a surge in mining activity in Madagascar. The country’s reserves include gold, cobalt, bauxite, and coal. It has the world’s largest sapphire reserves, and is one of the largest producers of chromite. Three projects receive particular attention from the global mining community: Rio Tinto’s ilmenite project is near Fort Dauphine in the far south, the Ambatovy nickel mine, and the Toliara mineral sands project. Ambatovy is situated some 80 kilometres east of Antananarivo and is a joint venture between Sumitomo of Japan and KOMIR of South Korea. Toliara is located in the far south-west of the island and is under development by Base Resources of Australia.

Heavy oil in western Madagascar was discovered around 1840. Modern extraction technology and high global oil prices have sparked interest in the island’s oil production potential. The two major onshore heavy oil fields are Tsimiroro and Bemolanga. Madagascar Oil owns Tsimiroro, and is in partnership with Total for the development of Bemolanga. While Madagascar imports crude petroleum, there are reports that its future prospects for oil production are promising.

Some social perspectives and impressions

As much as the flora and fauna of Madagascar is unique, so are the genetics of the Malagasy people. The Malagasy language is described as Austronesian, which indicates wide-spread origins from south-east Asia to Polynesia. While Asian descent is apparent, there has been immigration from Africa too. The population of the highlands interior have a strong Asian/Polynesian appearance, and those inhabiting the coastal areas are of clearer African descent. Sixty-one years of French colonisation has resulted in French social and linguistic influence.

Recent political upheaval

A political crisis developed in 2009 when a coup d’état by opposition leader Andry Rajoelina used military support to oust President Marc Ravalomanana, who fled to South Africa. There followed five years of protests and considerable social unrest and the freezing of foreign aid. In 2014, the African Union lifted its suspension of Madagascar’s AU membership after peaceful elections and a restoration of constitutional order. Three elections have since followed. In November 2023, Andry Joelina secured a third term as president despite a low voter turnout and a boycott by opposition groups.

Signs of economic improvement

Didier Ratsiraka was president from 1976 until 1993, and then again from 1997 to 2002. During the first years of his first period of rule, he implemented a strong socialist policy. This led to the nationalisation of the economy and a major increase in poverty levels. His later reforms did not substantially alleviate his country’s predicament.

It has been difficult for the formal economy to develop sufficiently. This challenge is illustrated by the experience of the Shoprite group. The large South African food retailer arrived in the country in 2002, and announced its exit in 2021. A major reason for its departure was its inability to compete with the long-standing and well-established system of informal markets scattered throughout the country.

But despite the political uncertainties and worryingly high youth unemployment, there are clear signs of economic improvement. The World Bank has estimated growth in 2023 at 3,8% and has forecast 5% growth for 2024. The fiscal deficit declined from 6,4% of GDP in 2022 to 4,9% in 2023. Inflation is expected to drop to an average of around 5,5%. The economy has been boosted by increased mining production. The telecommunications and financial sectors are performing relatively well. Exports of agricultural products such as vanilla have improved. Tourism is healthy, and visitor arrivals have doubled since 2022.

Is it time to take another look at the ‘grand île’ as a business and investment destination?