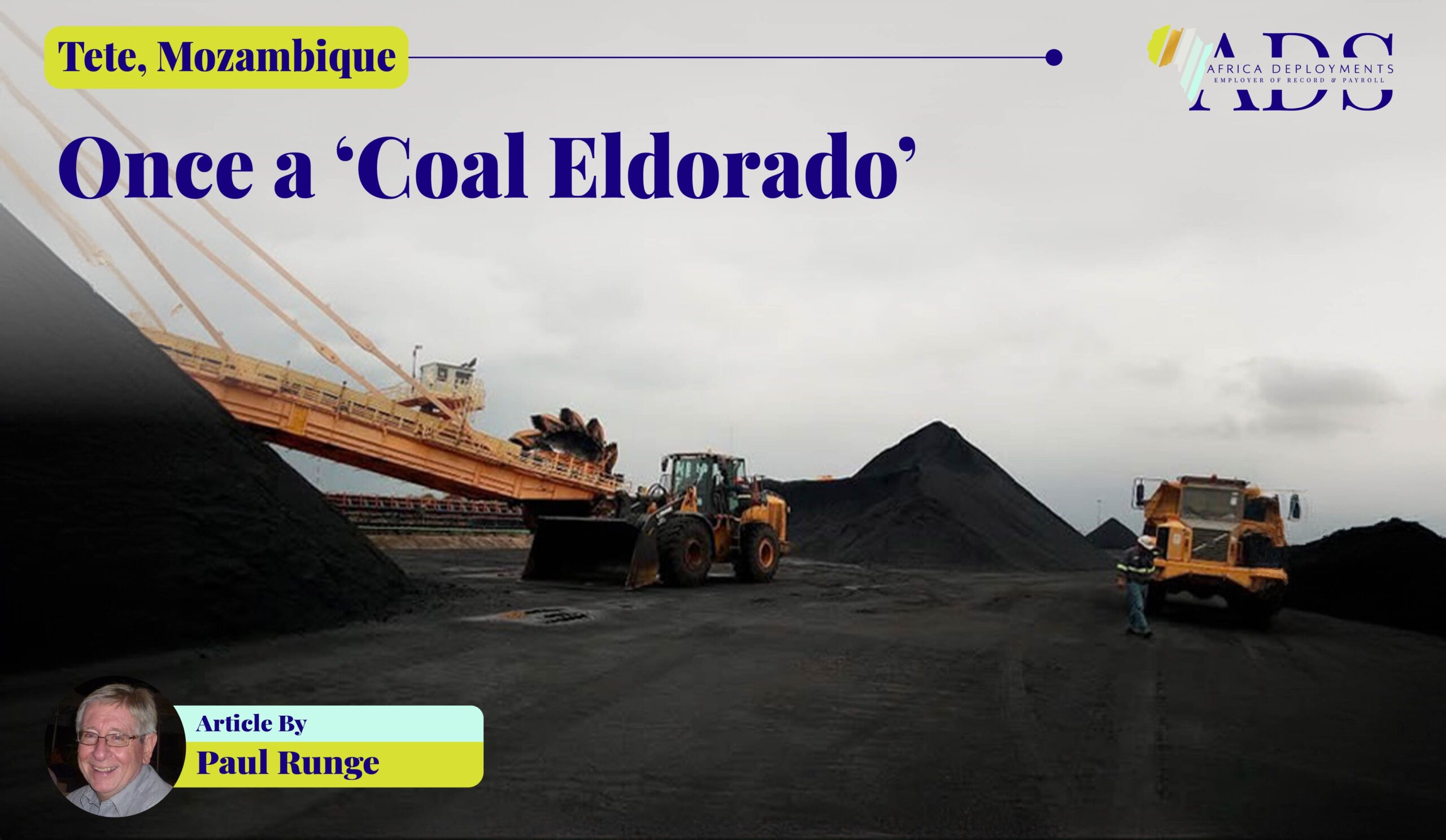

Tete, Mozambique: Once a ‘Coal Eldorado’

Did the Global Campaign Against Fossil Fuels Weaken Tete’s Potential?

A fast-growing ‘boom’ town…

I visited the Tete area in the Zambezi valley, central Mozambique several times from 2009 to 2013. The reason? So much was happening there. It was a ‘boom’ period. An Australian junior, Riversdale Mining had confirmed findings of steam or thermal coal (used largely for power generation), as well as coking or metallurgical coal (for steel manufacture). The latter is especially sought on the global markets, and the discovery drew considerable attention from investors, operators and suppliers.

These coal finds sparked the arrival of ancillary support infrastructure and services to the small town which at the time had a population of about 190 000. (Today, the number of inhabitants is estimated at around 320 000.) Land was allocated for a new industrial park. Yellow goods suppliers such as Bell Equipment and engineering firms such as WBHO and Group Five set up supply yards. The South African hardware retailer, Builders Warehouse, established a fair-sized operation. The major supermarket group Shoprite opened a store, new hotels were built and more restaurants opened up. Land for industry, commerce, offices and homes became increasingly sought after. The bridge over the Zambezi River which runs through the town, was widened to accommodate two-way traffic.

A proliferation of coal mines…

The Tete Province reportedly holds coal reserves of some 6,7 billion tons, of which nearly half are commercially viable. The list of coal mining operations in the Tete area is long. In 2008, 42 companies held coal mining licences in Mozambique, with nearly all of these based in Tete Province.

Most prominent of the mines is Moatize, which was originally operated by Riversdale. This mine produces over 11 million tons per annum. The Australian miner was also working the Benga concession. Another early entrant was Ncondezi Energy of the UK which initiated the Ncondezi coal project. The Chirodzi mine was developed by Jindal Africa of India. The Eurasian Natural Resources Company (ENRC), was awarded coal mining concessions, mainly for the production of thermal coal. Nippon Steel and the Sumitomo Metal Corporation were granted a concession for the Revuboe coal prospect with the objective of mining coking coal.

And then the big boys came in…

In 2011, the giant resources group, Rio Tinto, began taking over the operations of Riversdale with a bid amounting to almost US$ 4 billion. Rio initially based its acquisition of Riversdale’s Benga mine on the promise of a high percentage of coking coal, and transport of mine production to the coast by way of barges on the Zambezi River.

In 2008, the world’s biggest iron ore producer, Vale of Brazil, announced that it was taking over the Moatize coal concession and would be investing US$ 250 million in the Mozambican coal sector. It had won a 25-year concession for the operation of Moatize.

In early 2011, the Mozambican authorities awarded Jindal Steel & Power of India a 25-year licence to explore and mine for coal in Tete Province. The company announced an investment of US$ 180 million when it took over the Chirodzi coal mine, which was officially inaugurated in 2013.

During my business missions to Tete, I tried to make direct contact with the mining operating companies to gain first-hand information on developments. My experience was mixed. I had no trouble securing meetings with Riversdale at their offices outside the town. I was pleasantly surprised to be well received by Riversdale’s successor, the major mining house, Rio Tinto. Jindal’s main offices were at their Chirodzi mine site, but I met with junior officials of the company at their support office located near the Tete town centre. However, all my attempts at meeting with Vale, failed. I wasted a good number of hours waiting at security outside the Moatize mining area for permission to enter. But the green light was never given, despite my confirmation that I was representing several mining supply companies.

Major investment in a coal export transport route…

A major question for the mining operators was how to transport their production to the coast for export. Initially, there was much reference to the 660-kilometre Sena rail line that links Tete to Beira Port. However, the line required considerable rehabilitation and coal handling facilities at Beira Port. Another idea was for the barging of coal on the Zambezi River to a new port. But the government rejected this proposal, mainly due to environmental considerations.

In 2017, Vale and Mitsui of Japan announced that they had agreed to invest US$ 3 billion in the development of the Nacala Integrated Logistics Corridor. This alternative route included a 912-kilometre rail line (new and rehabilitated), passing through Malawi on its way to the deepwater port of Nacala on Mozambique’s northern coast. The initiative also included the installation of bulk coal handling facilities at a dedicated port extension at Nacala-a-Velha.

And then departures as the major miners turn away from coal…

In mid-2014, Rio Tinto agreed to sell its Benga mine as well as its other mining interests in Tete to International Coal Ventures Private Limited (ICVL) of India for a mere US$ 50 million, (despite Rio’s investment totalling about US$ 3,7 billion.) It claimed that the assets it had bought from Riversdale were not as good as the company had originally thought. Other reasons were falling global coal prices and logistics issues.

Then in late 2021, the major role player, Vale announced that it was selling its Moatize mine and the connected Nacala rail line to Vulcan Minerals, a subsidiary of Jindal, for only US$ 270 million. The Brazilian giant indicated that it no longer wished to own coal assets.

In 2022, Ncondezi Renewables announced that it was moving away from coal, and would be establishing a 300 MW solar power plant at its mine site in Tete. The reasons given for this decision referred to uncertainties following China’s announcement that it was pulling funding of coal projects abroad. (Ncondezi had been partnering with China Machinery Engineering Corporation for development of a coal-fired power plant at its mine.)

Has the global campaign against fossil fuels played a role in Tete’s coal evacuation?

The Indian companies, Jindal/Vulcan and ICVL have remained in Tete. India has a strong demand for coal to feed its major iron and steel industries.

It is clear that within the global context, many funding agencies (including development finance institutions) are curtailing their support for fossil fuel projects. In the case of coal mining in Tete, a number of non-governmental organisations (NGO’s) are reporting environmental damage caused by the flurry in coal mining activity over the last decade. They emphasise the plight of local communities who complain of lost agricultural land, homes and clean water supply.

Vale and smaller operators such as Ncondezi have made clear announcements of their shift away from coal. Rio Tinto’s earlier departure may have been based mainly on factors other than those of an environmental nature. However, it too has since produced its climate change position statement which emphasises carbon capture technology and low-carbon emissions.

The extent to which the campaign against fossil fuels actually prompted the departure of these companies from Tete is unclear. But logically, it should have exerted a substantial influence.