DR Congo: The Kinshasa-Matadi Transport Corridor A Vital Link Receives Attention

An important announcement on a long-delayed rail project…

In August 2023, an interesting news item appeared on my computer screen. It was headed: “The rehabilitation of the Kinshasa-Matadi railway: a crucial step for the economic development of the DRC.”

The report reminded me of a meeting I’d had with the DRC Ministry of Transport in Kinshasa in August 2013. Arriving on time, I spent about an hour waiting in the ministry’s foyer. The apology for the delay (which came from the secretary), was followed by an explanation that the officials were busy in a very important meeting with representatives of a major development bank. The ministry and the bank officials were discussing possible funding for studies on the rehabilitation of the 366-kilometre Kinshasa-Matadi rail link.

Kinshasa is the chaotic, crowded capital, and is the main commercial centre of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Matadi is the port situated 150 kilometres upstream on the Congo River and the smaller port of Banana on the Atlantic Ocean. Matadi is capital of the Bas Congo Province, and is the ‘feeder’ port for supply to the over 17 million inhabitants of the Kinshasa area. The rail and road transport corridor linking the two centres is therefore of prime importance.

My mission

A major industrial company was planning to construct a factory in the Kimpes area. Kimpese is a small town which lies about two-thirds of the way from Kinshasa to Matadi. My main mission was to verify Matadi Port’s vaibility for the handling of goods exported from their envisaged plant as well as for the importation of the factory’s operational requirements. I was tasked with ascertaining how well the transport corridor was operating.

My Kinshasa-Matadi road adventures…

Prior to starting out for Matadi, my appointed driver, Jean-Pierre, informed me that the 347,5 kilometres on the N1 highway would take longer than the seven hours I had been told. “There are a few problems,” he muttered.

Our first problem was getting out of Kinshasa. The city environs seemed to stretch on forever, and it took some hours before the dilapidated buildings and shanties and crowds of roadside sellers gave way to green fields dotted with trees and clumps of tropical bush. At one stage, we passed through a shady tunnel created by the bamboo trees which grew on both sides of the road reaching over and intertwining into a long arch.

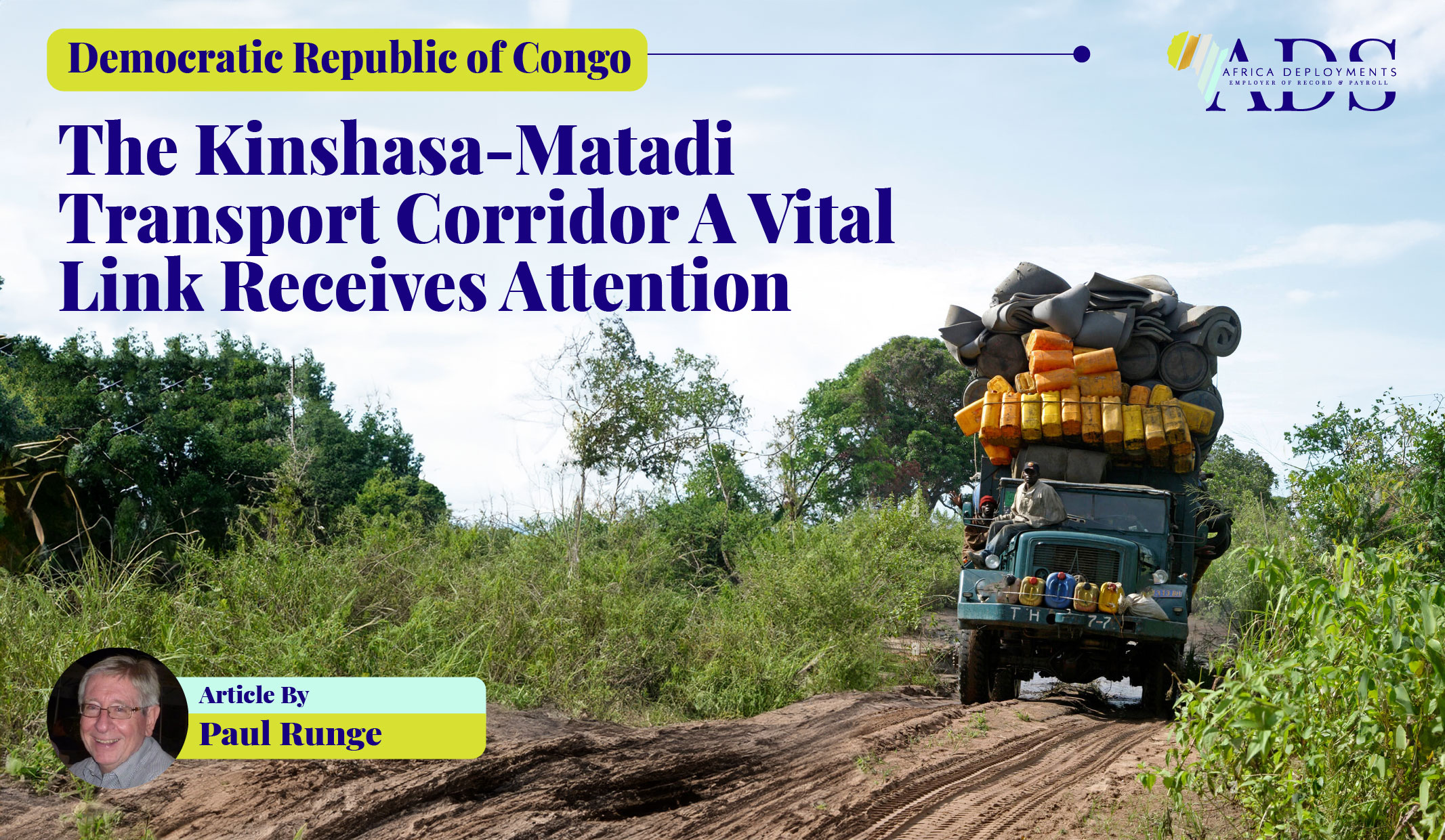

Another problem was the many slow-moving, greatly overloaded vehicles and buses that we had to dodge. Old trucks loaded up to more than twice their height with bags and crates and furniture and other items, teetered at precarious angles as they snaked their way along the bumpy and cracked tarmac. One, two or sometimes three passengers lay sprawled at the top of the cargo piles, miraculously clinging on as the trucks swayed alarmingly around the bends. Another mutter from Jean-Pierre: “All these overloads. This road will never last.”

There were three tolls though which we had to pass. The payment procedure at these tolls was very different to usual international toll procedures. We were obliged to stop, get out of our vehicle, and walk up to a few bored officials sitting at a rickety table. After much discussion we made payment (8 500 Congolese Francs for a 4×4), and were handed a slip of paper which we were sternly warned to show at the next toll stop. Maybe Jean-Pierre and I were too busy talking, because we somehow drove through the second toll without paying. This serious omission caused considerable consternation at the third toll, and much time was wasted while Jean-Pierre driver negotiated the fee plus penalty with the angry officials.

Arrival in Matadi…

The outskirts of the port city constitute one huge informal market. Progress was very slow as we wove our way through crowds of sellers strolling on the streets, pleading and proffering their goods to passing drivers and passengers. Fruit in baskets, ground nuts in old liquor bottles, water in sachets, cold drinks in cooler boxes, soccer jerseys on hangers, flags on sticks, toys in boxes, newspapers and magazines in bundles….

The main port entrance was blocked with lines of trucks, but we found another small entrance. I walked down to the port authority offices. The old building was filled with shouting and gesticulating staff and their apparent customers. A harassed old man in jeans and t-shirt wearing a port authority cap, made it clear to me that my chances of obtaining an authorised visit to the port were very slim. “Today is a bad day. Very busy, Monsieur.” What was I to do? I needed to provide the client with a report on the port’s operations, including details such as tonnages, transit times and items imported.

I was walking up the hill back to the entrance when to my immense relief, I saw a double-storey building emblazoned with the blue and white colours of a major international freight forwarding firm – a good client company which was bound to render much-needed assistance.

An important port receives some attention…

One of the senior company representatives, a Frenchman who had spent six years in the DR Congo, took me to the top floor of the building where we were able to get a good view of the port complex. He pointed out the quays, warehouses and rail lines. A few vessels were docked.

“There are ten quays but some are not operating. There have been some improvements. Two quays have recently been rehabilitated. There is a shortage of warehouses. This is why much offloading is done directly from truck to vessel. There isn’t much rail activity. We only see movement on that rail line about once a month. There’s a need for dredging. The depth is only about 6,7 metres. A South African dredging company was recently busy here. The current waiting time for vessels is twelve days.“

A return journey turns into a rescue mission…

We had just left Matadi and were on our way back to Kinshasa when my cell phone beeped. Three geologists working for my client had been stuck for some days in Kimpese, the message said. Could I please pick them up?

We found the three bedraggled scientists waiting for us on the side of the N1.

“We were taking soil samples on the site of the planned factory. This place is chaotic, but there’s a helluva lot of potential.”

The three were in the back seat, gratefully slurping the cold Cokes we’d handed them.

“Thanks for the lift”, one of them said. “We’ve been waiting here for a bloody long time. We almost ran out of supplies. It’s been as hot as hell. Thank goodness we had a good stock of liquid refreshment. We’ve had enough Primus Beer to stock a brewery.”